Our forests are in crisis.

Forests across the Eastern Sierra are facing an unprecedented crisis. Once characterized by large, widely spaced trees, open understories, and vertical and horizontal heterogeneity, these ecosystems are now homogenous and dense with many small, tightly packed trees with increasing mortality leading to vastly higher surface fuel loads over time.

This shift has led to a troubling increase in high-severity wildfires that fundamentally alter forest ecosystems and threaten their resilience. In the last decade, California has seen 9 of 10 of its largest wildfires, and the area burning at high severity has surged – from 10% in 1850 to 43% today.

Historically, high-severity fires would typically affect small patches of land, which were part of a diverse, natural fire regime. Today, large, uncontrollable high-severity fires can strip entire landscapes, posing significant risks to wildlife, water quality, and human safety with long-term consequences that could devastate local landscapes and economies.

How did we get here?

For thousands of years, wildfires were a natural and essential component of California’s forest ecosystems. Lightning-caused fires would occur regularly, often in the summer months, igniting the landscape and helping to maintain healthy forests. These fires were typically low- to moderate-severity, consuming dead vegetation and thinning small trees while sparing mature, fire-resistant trees.

In parallel, Indigenous communities actively managed portions of the landscape through cultural burning practices, using fire to tend plants they used and that provided food sources for the wildlife they depended on. These regular, low-intensity burns helped to prevent the accumulation of excess fuel and kept the forests in a healthy, resilient state.

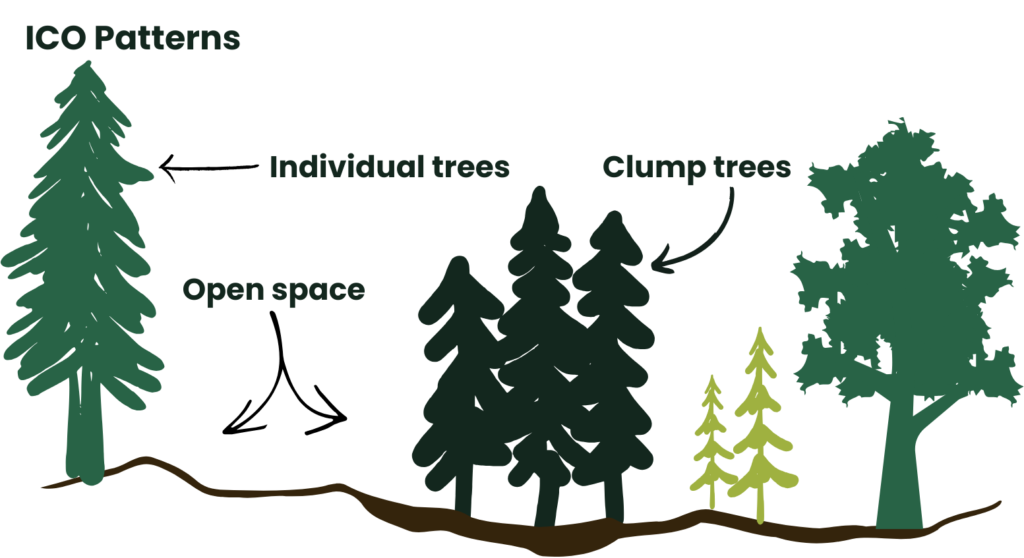

Historically, these frequent fires contributed to a diverse forest structure also known as forest heterogeneity. This natural variation included a mix of tree ages and densities, creating patches of individual trees, clumps, and open areas (known as the ICO pattern), which supported greater biodiversity and reduced the likelihood of large-scale high-severity fires.

Fire fighters going to the front, Lassen National Forest, 1927. Source: foresthistory.org

However, the arrival of European settlers in the 19th century marked a significant shift in land and fire management. With the spread of settlements, ranching, and logging, large-scale fire suppression policies became the standard.

By the early 20th century, the U.S. Forest Service had institutionalized these fire suppression strategies as a cornerstone of forest management. In 1935, the “10 a.m. policy” was introduced, requiring that any fire reported in the national forests be controlled by 10 a.m. the following day. The objective was to suppress wildfires quickly to protect timber resources, property, and lives.

While these policies were well-intentioned, they disrupted the natural fire cycles that had kept forests healthy and balanced. With each decade of fire suppression, fuels accumulated in the form of dead vegetation and densely growing trees, creating conditions that allowed smaller, low-severity fires to escalate into intense, destructive blazes.

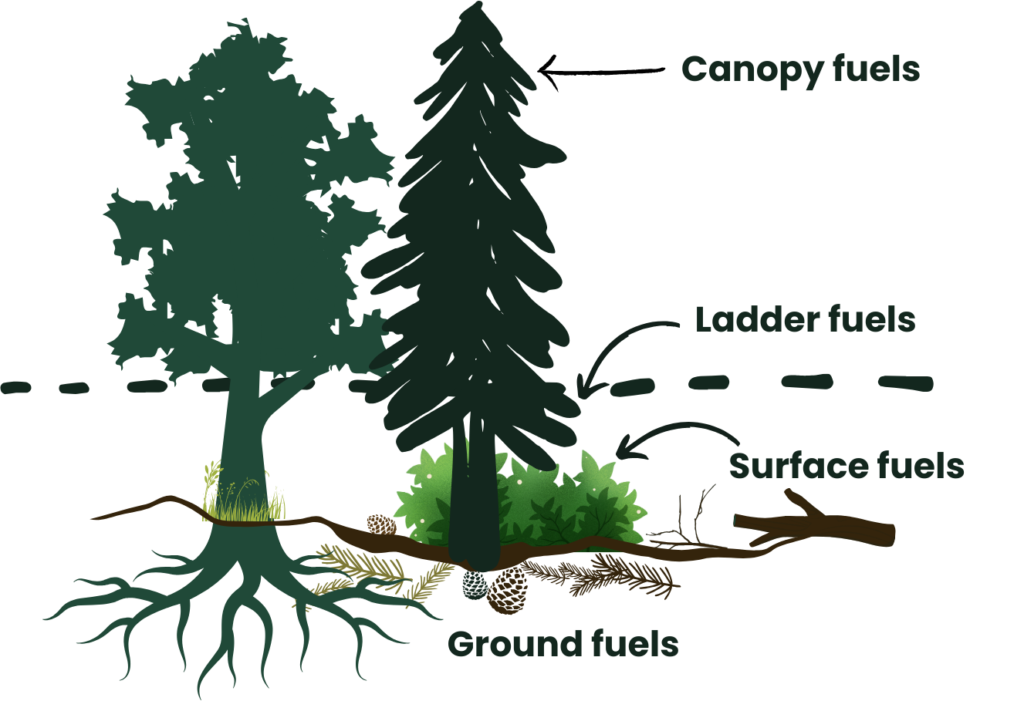

By the mid-20th century, a forest that might once have had about 65 trees per acre could have upwards of 500 trees per acre. This high tree density creates dangerous “ladder fuels” that carry fire from the ground up into the canopy and a continuous canopy with interlocking crowns allowing fire to spread more rapidly and be more destructive.

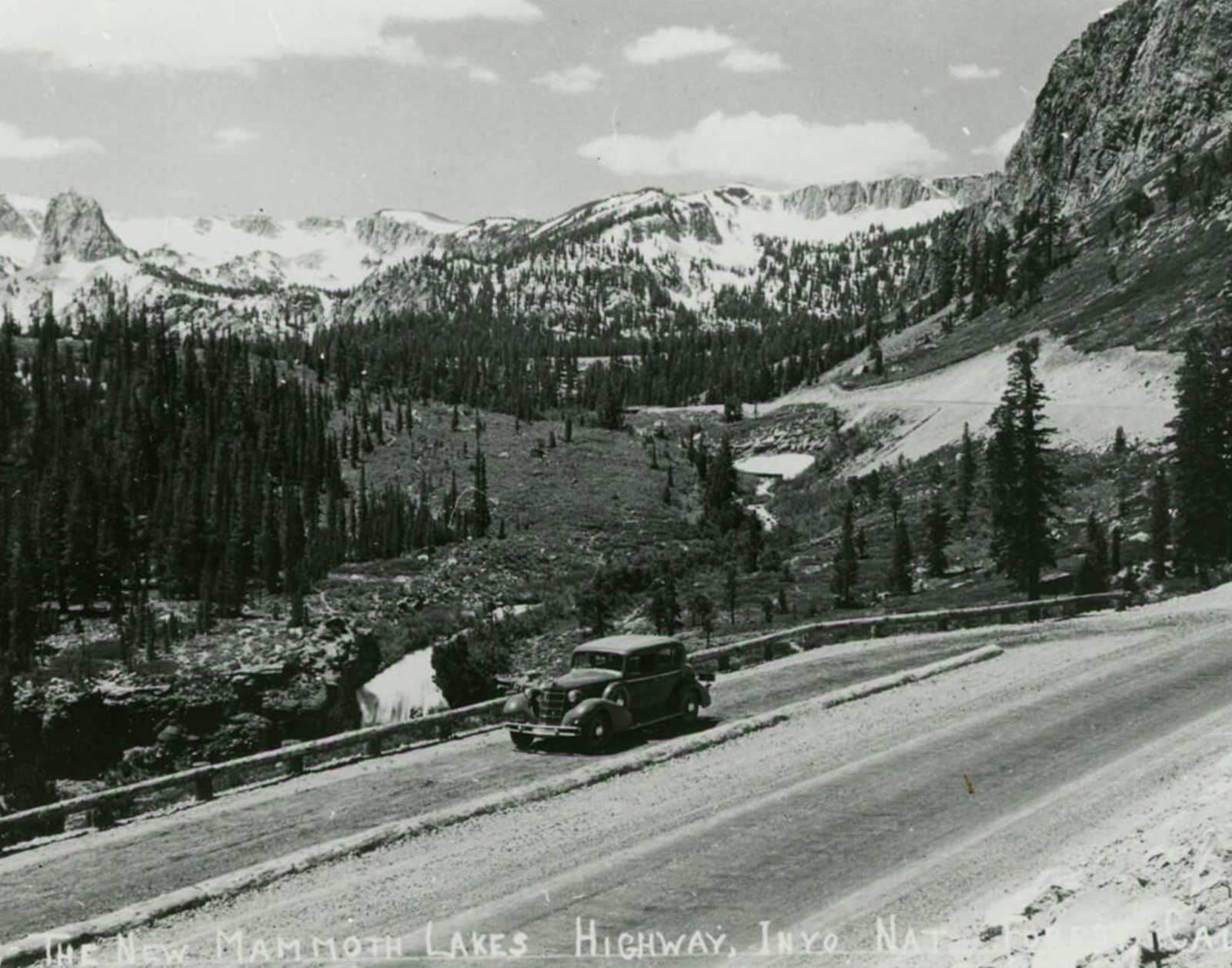

Move the slider to view how forest density has changed in Mammoth Lakes. Left photo: Stephen Willard, est. 1930s. Right photo: Bruce Willey, 2023.

Fire suppression was not the only policy shift that worsened forest health. Logging practices in the mid-20th century removed many of the largest, most fire-resistant trees, replacing them with dense plantations. These younger, more vulnerable trees added to the fuel load and further increased the potential dash for large scale high-severity fires.

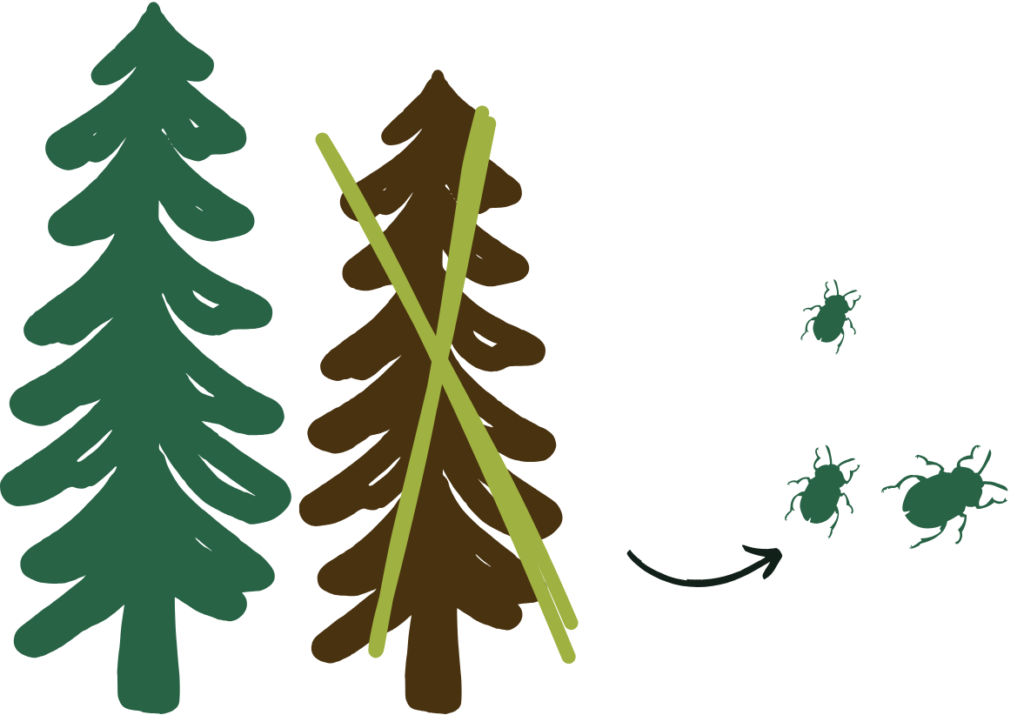

The disruption of natural fire cycles also facilitated the spread of pests and diseases, like bark beetles, that thrive in dense, weakened forests. Combined with climate change’s intensifying effects, such as prolonged drought and rising temperatures, these conditions have created a perfect storm for wildfire disasters.

In recent decades, the consequences of these fire suppression policies have become increasingly evident. Wildfires are burning hotter, spreading faster, and causing greater ecological and economic damage than ever before, yet reversing over a century of suppression is a complex challenge.

What’s at risk?

Click the drop down arrows to learn more about what is at risk.

Without intervention, forests continue to weaken, with overcrowded trees struggling for survival, which increases tree mortality and reduces forest resilience to pests, pathogens, drought, and other stressors.

Dense, unhealthy forests are prime targets for pests like the bark beetle, which can decimate weakened trees.

Homogenous, dense forests enhance wildfire risk and reduce forest health. Dense canopies that reduce light availability suppress the growth and establishment of species that are sun-loving and fire and drought resistant, leading to a less resilient forest.

The severity and intensity of wildfires are growing, with over half of California’s deadliest fires occurring this century and many of the most destructive fires happening since 2019.

Current forest conditions include ladder fuels and continuous canopies. Ladder fuels allow a fire to climb from the forest floor into the canopy, where it can spread rapidly when canopies are continuous.

Large scale high-severity fires release massive amounts of greenhouse gases, with forest fires in 2020 emitting approximately 112 million metric tons of CO₂—almost a quarter of California’s annual emissions.

Severe fires destabilize soil, leading to erosion, degraded water quality, and heightened flood risks. Watersheds affected by high-severity fires may experience up to 10 times the normal runoff and erosion.

High-severity fires can devastate essential habitats, threatening the survival of vulnerable species that rely on forests.

Forests with excessive canopy cover lose more water through evapotranspiration. Thinning trees in these areas can restore groundwater levels and significantly increase streamflow.

What We Can Do

Investing in Mitigation and Science-Based Treatments

The solution lies in proactive forest management based on the best available science. Research shows that each dollar spent on wildfire prevention saves up to $6 in response and recovery costs, a critical impact for a crisis costing the U.S. economy as much as $893 billion annually. Treatments like strategic thinning and prescribed burning are essential to restoring natural fire cycles and reducing fuel loads. A 20-year study demonstrates that treated areas have an 80% chance of withstanding wildfire, highlighting the effectiveness of these approaches. By using data-driven approaches, we can implement ecosystem-specific prescriptions to support a diverse range of forest types in the Eastern Sierra.

How Fuels Reduction Helps

Fuels reduction is a critical tool in mitigating the intensity of wildfires and restoring the health of forest ecosystems. Two primary methods of fuels reduction—thinning and prescribed burning—target the accumulation of excess vegetation and dead biomass, which contribute to the rapid spread and severity of wildfires. Both methods work in tandem to restore natural fire cycles and create conditions that are more resilient to climate change.

Thinning: Creating Space for Healthy Forests

Thinning is a forest management technique that involves selectively removing trees and vegetation to reduce forest density. Thinning is particularly beneficial in forests that have become overcrowded due to fire suppression and other management practices over the past century. Thinning helps improve forest health by:

Reducing Fuel Loads

By removing excess live and dead trees, understory vegetation, and surface fuels thinning decreases the amount of combustible material in the forest. This is particularly important in areas where dense vegetation has accumulated over decades of fire suppression. With less fuel to burn, fires are less likely to become catastrophic or uncontrollable, or burn at high severity.

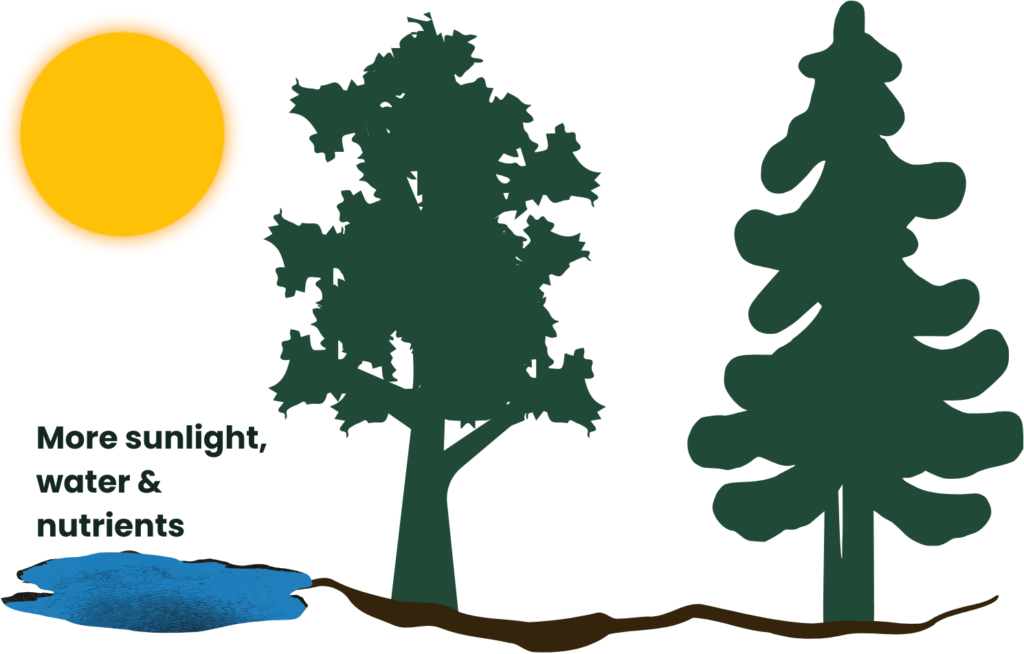

Improving Tree Growth

Overcrowding in forests forces trees to compete for water, nutrients, and sunlight. Thinning helps reduce this competition, allowing remaining trees to be healthier and more vigorous.

Increasing Forest Resilience

Healthy forests are more resilient to pests, diseases, and droughts. Thinning improves tree health by reducing stress and allowing more sunlight and water to reach each individual tree. Thinning also helps reduce the spread of forest pests like bark beetles, which thrive in stressed, crowded forests.

Improved Forest Structure

Strategically applied, thinning can create ICO patterns—individual trees, groups of clumped trees, and open spaces—that enhance forest heterogeneity, mimicking natural structures found in historically resilient forests.

Prescribed Burning: Restoring Natural Fire Cycles

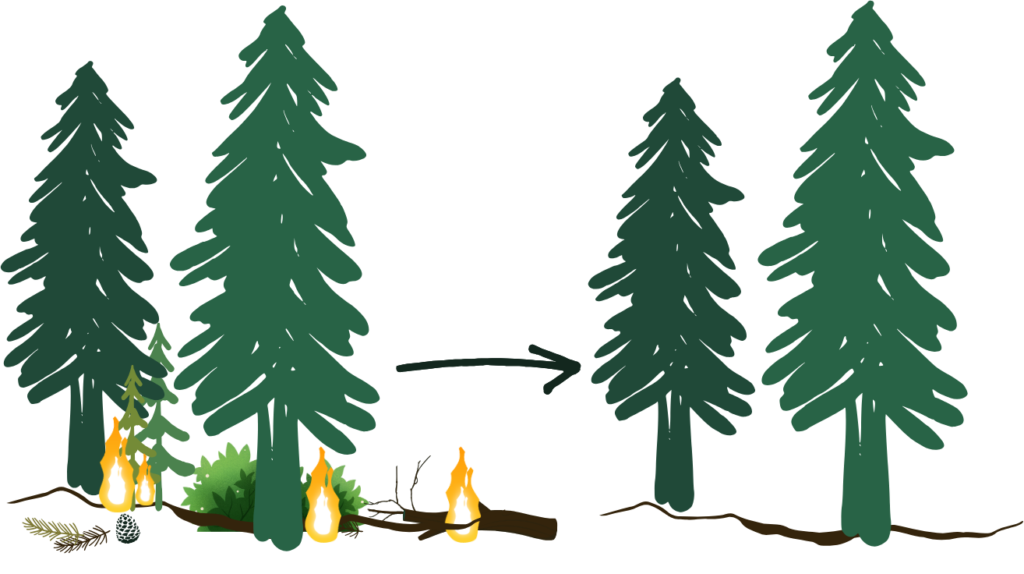

Prescribed burning (also known as controlled or intentional burning) is another important tool in fuels reduction. This technique involves deliberately setting fires under controlled conditions to reduce the amount of combustible vegetation in a forest. Prescribed burns are carefully planned and executed by trained professionals to ensure they are safe and effective. The benefits of prescribed burning include:

Reducing Understory Fuels

Prescribed burning removes accumulated dead vegetation, small trees, and brush, which can serve as ladder fuels in a wildfire. By reducing these fuels, prescribed burns prevent the occurrence of dangerous and intense fires that kill the whole tree, also known as “crown fires.”

Restoring Ecological Balance

Many ecosystems in the Eastern Sierra, including pine forests, evolved with regular, low- to moderate-severity wildfires. These fires maintained open forest canopies, promoted biodiversity, and helped control the spread of disease and pests. Prescribed burns mimic these natural fire cycles, allowing forest ecosystems to return to a more resilient, balanced state.

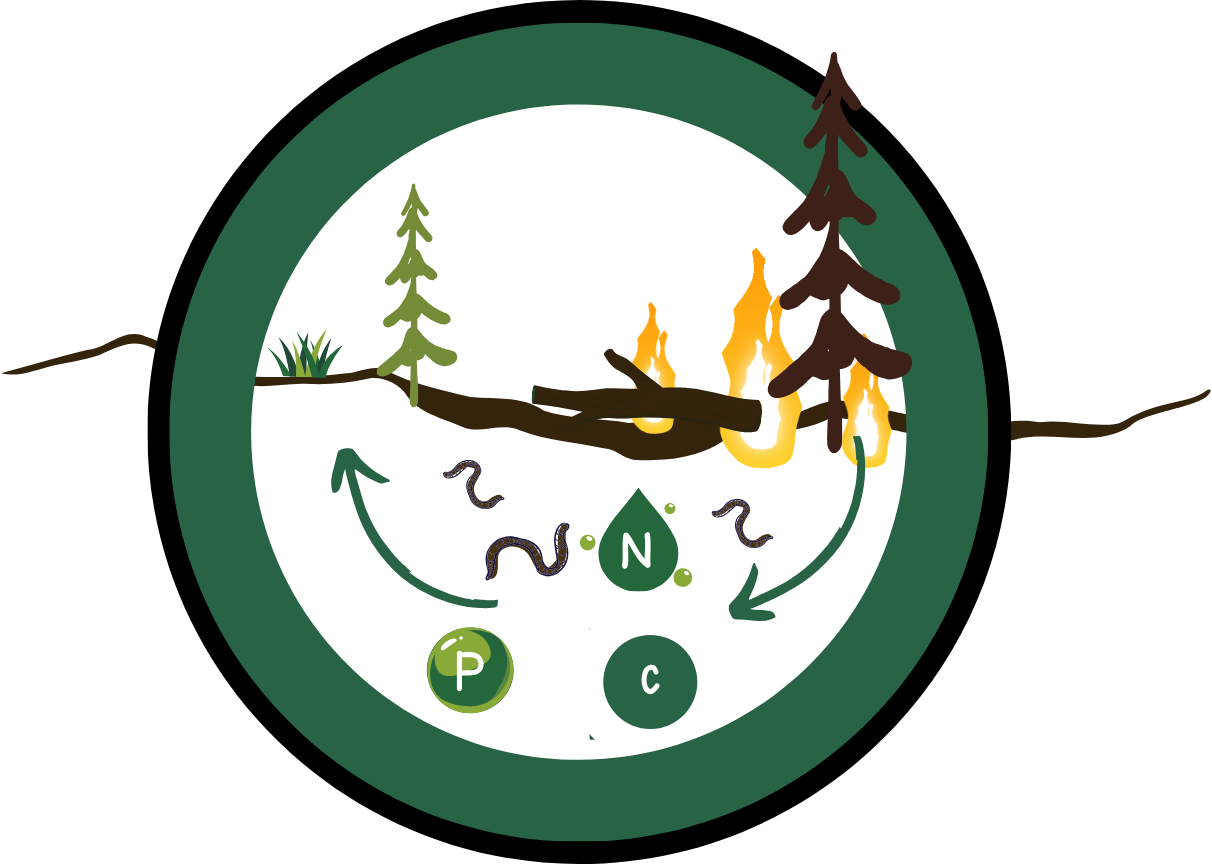

Nutrient Cycling

Fire plays an essential role in nutrient cycling within forest ecosystems. When vegetation is burned, nutrients are released back into the soil, enriching it and promoting the growth of new plants. This is especially beneficial for plants that are adapted to fire-prone environments, such as certain species of shrubs, grasses, and trees.

Reducing the Risk of Larger, Uncontrollable Fires

By intentionally burning smaller, manageable patches of vegetation, prescribed burns help to reduce the fuel load across larger areas of the forest. This minimizes the likelihood of wildfires escalating into high-intensity, catastrophic events. These controlled burns also help fire crews manage fire risks more effectively by reducing fuel in key areas.

Synergistic Effects of Thinning and Prescribed Burning

Thinning and prescribed burning are not only complementary but also mutually reinforcing. Thinning alone can reduce fuel loads, but prescribed burning further reduces the buildup of fine fuels, such as dead grass, small brush, and leaves. This combination of methods help forests become healthier and more resilient, especially in regions where fire suppression has caused significant ecological imbalance.

In many cases, thinning is done first to reduce fuel loads and create more space between trees before a prescribed burn is conducted. This helps fire remain low-intensity and controlled. Together, these techniques can help to reintroduce natural fire cycles, reduce the risk of extensive high-severity wildfires, and restore forests to a state where they can thrive.

Aerial photos show how different treatment areas responded to the Bootleg Fire, 2021. Source: Steve Rondeau, Klamath Tribe.

Co-Benefits of Fuels Reduction

As we reduce fuel loads and restore fire-resilient conditions, we also unlock significant co-benefits that contribute to ecosystem restoration, community resilience, and broader environmental goals. These co-benefits are just as essential to the future health of our forests, water resources, and local economies. Explore how these integrated solutions can have far-reaching impacts beyond just reducing the threat of catastrophic wildfires.

High-severity wildfires are among the leading threats to the ongoing survival of many threatened and endangered species due to the potential loss of habitat and elimination of movement corridors. Our efforts focus on enriching habitat diversity and complexity, restoring forests to their natural densities and structure, which in turn enhances our ability to respond to wildfires that endanger these habitats. This directly benefits all species in the Eastern Sierra including the Bi-State sage-grouse, Yosemite toad, and Sierra marten.

Millions of people visit the Eastern Sierra each year to experience its unparalleled recreational opportunities. This outdoor recreation-based tourism serves as the economic backbone for local communities. The looming threat of wildfire poses a significant risk, with the potential to fundamentally alter outdoor experiences and devastate local economies. It would take decades for our landscape to recover from a high-severity wildfire, and the places we all love would likely never look the same. Whitebark’s work is key to supporting the local economy and maintaining outdoor space and recreation opportunities for generations to come.

The effort we’re leading will yield sufficient woody material to justify the establishment of a bioenergy facility in the Eastern Sierra. This facility will be designed to generate three megawatts of reliable, clean electricity annually, using 28,000-35,000 dry tons per year of forest residuals once considered as waste. Through this initiative, we can offset an impressive 53,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent each year, while also contributing to fire mitigation and other carbon sequestration endeavors.

Severe wildfires can significantly degrade air quality, posing risks to human health and exacerbating respiratory issues. Proactive fuels treatments, including managed natural fire and prescribed burning techniques can reduce the threat of severe wildfires and associated air pollution. By reducing fire intensities and limiting burning durations, Whitebark’s work helps mitigate the short-term health impacts of smoke and airborne pollutants, contributing to the well-being of communities and visitors in the Eastern Sierra and beyond.

Our work is centered in vital watersheds that serve as lifelines for millions of Californians, fulfilling over a third of Los Angeles’ annual water requirements. Yet, the reliability of this crucial water source faces threats from wildfires and forest degradation. Through strategic measures to reduce the unnaturally dense tree cover in Eastern Sierra forests, we can revive streamflow to pre-fire suppression levels. This restoration effort not only bolsters water security for the entire state and its residents but also provides a vital resource as other water supplies face increasing pressure. content.

High-severity wildfires are among the leading threats to the ongoing survival of many threatened and endangered species due to the potential loss of habitat and elimination of movement corridors. Our efforts focus on enriching habitat diversity and complexity, restoring forests to their natural densities and structure, which in turn enhances our ability to respond to wildfires that endanger these habitats. This directly benefits all species in the Eastern Sierra including the Bi-State sage-grouse, Yosemite toad, and Sierra marten.

Millions of people visit the Eastern Sierra each year to experience its unparalleled recreational opportunities. This outdoor recreation-based tourism serves as the economic backbone for local communities. The looming threat of wildfire poses a significant risk, with the potential to fundamentally alter outdoor experiences and devastate local economies. It would take decades for our landscape to recover from a high-severity wildfire, and the places we all love would likely never look the same. Whitebark’s work is key to supporting the local economy and maintaining outdoor space and recreation opportunities for generations to come.

The effort we’re leading will yield sufficient woody material to justify the establishment of a bioenergy facility in the Eastern Sierra. This facility will be designed to generate three megawatts of reliable, clean electricity annually, using 28,000-35,000 dry tons per year of forest residuals once considered as waste. Through this initiative, we can offset an impressive 53,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent each year, while also contributing to fire mitigation and other carbon sequestration endeavors.

Severe wildfires can significantly degrade air quality, posing risks to human health and exacerbating respiratory issues. Proactive fuels treatments, including managed natural fire and prescribed burning techniques can reduce the threat of severe wildfires and associated air pollution. By reducing fire intensities and limiting burning durations, Whitebark’s work helps mitigate the short-term health impacts of smoke and airborne pollutants, contributing to the well-being of communities and visitors in the Eastern Sierra and beyond.

Our work is centered in vital watersheds that serve as lifelines for millions of Californians, fulfilling over a third of Los Angeles’ annual water requirements. Yet, the reliability of this crucial water source faces threats from wildfires and forest degradation. Through strategic measures to reduce the unnaturally dense tree cover in Eastern Sierra forests, we can revive streamflow to pre-fire suppression levels. This restoration effort not only bolsters water security for the entire state and its residents but also provides a vital resource as other water supplies face increasing pressure. content.

High-severity wildfires are among the leading threats to the ongoing survival of many threatened and endangered species due to the potential loss of habitat and elimination of movement corridors. Our efforts focus on enriching habitat diversity and complexity, restoring forests to their natural densities and structure, which in turn enhances our ability to respond to wildfires that endanger these habitats. This directly benefits all species in the Eastern Sierra including the Bi-State sage-grouse, Yosemite toad, and Sierra marten.

Millions of people visit the Eastern Sierra each year to experience its unparalleled recreational opportunities. This outdoor recreation-based tourism serves as the economic backbone for local communities. The looming threat of wildfire poses a significant risk, with the potential to fundamentally alter outdoor experiences and devastate local economies. It would take decades for our landscape to recover from a high-severity wildfire, and the places we all love would likely never look the same. Whitebark’s work is key to supporting the local economy and maintaining outdoor space and recreation opportunities for generations to come.

The effort we’re leading will yield sufficient woody material to justify the establishment of a bioenergy facility in the Eastern Sierra. This facility will be designed to generate three megawatts of reliable, clean electricity annually, using 28,000-35,000 dry tons per year of forest residuals once considered as waste. Through this initiative, we can offset an impressive 53,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent each year, while also contributing to fire mitigation and other carbon sequestration endeavors.

Severe wildfires can significantly degrade air quality, posing risks to human health and exacerbating respiratory issues. Proactive fuels treatments, including managed natural fire and prescribed burning techniques can reduce the threat of severe wildfires and associated air pollution. By reducing fire intensities and limiting burning durations, Whitebark’s work helps mitigate the short-term health impacts of smoke and airborne pollutants, contributing to the well-being of communities and visitors in the Eastern Sierra and beyond.

Our work is centered in vital watersheds that serve as lifelines for millions of Californians, fulfilling over a third of Los Angeles’ annual water requirements. Yet, the reliability of this crucial water source faces threats from wildfires and forest degradation. Through strategic measures to reduce the unnaturally dense tree cover in Eastern Sierra forests, we can revive streamflow to pre-fire suppression levels. This restoration effort not only bolsters water security for the entire state and its residents but also provides a vital resource as other water supplies face increasing pressure.

Get Involved

Take action for healthier forests—sign up for updates or donate now to support impactful solutions.

Make a Donation Subscribe to Emails